Writing Fantasy

In September 2003, Chaz was invited to Korea, to speak at the UK-Korea Fantasy Forum, organised in response to a recent boom in public interest in British fantasy literature among both readers and publishers in Korea - the popularity of the Harry Potter books and the recent film incarnations of The Lord of the Rings may go some way to explain this. The Forum was co-hosted by the British Council, the Daesan Foundation and the Korean Association for Literature and Film.

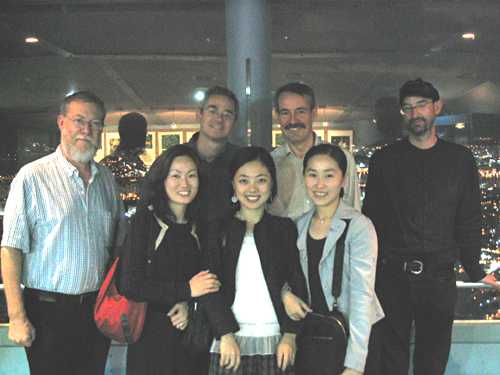

Pictured above at the Seoul Tower are some of those who attended the Forum: the men, from left to right, are John Jarrold, now a freelance but previously an editor at Orbit books (UK publishers of The Books of Outremer), children's author Cliff McNish, Dr Brian Rosebury, a fantasy literature academic and Chaz; the women are the British Council's Sunah You, Hyang-A Lee and Yoomie Goh.

Other guests were, from the UK, Professor Peter Hunt, a children's fantasy literature academic, and Korean writers and academics, including Mr Young-Do Lee, the most popular fantasy writer in Korea, and Professor Sung-Kon Kim, one of the most notable professors of English literature in Korea.

What follows is the text of Chaz'z contribution to the Forum, entitled, as the Korean text says, Writing Fantasy.

From our very earliest days on this planet, as soon as we had language to work with, human beings have told each other stories. That's one of the ways that language developed, and one of the reasons too. As soon as something has a name, you can talk about it when it isn't there; you don't have to point and say 'that thing there', you can just say 'tiger' and everyone understands. And as soon as you can do that, you want to do more than that, you want to say something useful about the tiger; so you need other words and other kinds of words, you want to be able to say that the tiger is asleep, or the tiger has gone away, or the tiger has eaten the chief and is coming up the hill.

You never need to say that the tiger is dangerous, because the whole tribe knows that, the word is an alarm call in itself. So one night one of the clan hunters is out in a storm, and when he comes back to the cave he's shivering and frightened, and he says that the storm is a tiger; and people know what he's saying, that the wind and the rain are like the tiger's teeth and claws, fierce and sharp as they tear at your skin, and the thunder is like the tiger's roar as it echoes in the hills. And so the hunter has invented metaphor, he's learned to say that one thing

is like another; and the old wise woman has been listening to him because she's old and wise, and when she wants to warn the children not to go outside the cave when a storm is coming, she says, "Some days the storm-god comes hunting through the hills like a tiger, looking for little ones to eat; and his eyes are fire like the lightning but his breath is cold and deadly, and the leaves shiver on the trees before he comes and all the little animals hide in holes and so do we, here in our cave," and so she's invented description, illustration, pictures in words. And

one little boy doesn't listen, or else he's foolishly brave, and so he gets caught outside in a storm and he never comes back to the cave; and his sister remembers, and when she is old and wise in her turn, what she says to her own children is this:

"Once long ago I had a brother, whose name was Stupid, because he never listened to the wise woman who knew more than he did. And so he went out into the forest when he shouldn't, because the storm-tiger's breath was blowing across the sky in great dark angry clouds, and its voice was rumbling and roaring in the hills, and the bravest hunters in the tribe were all staying close inside the cave that day. But my brother Stupid went outside, and he met the storm-tiger in the trees. He heard it coming in the rustle of the leaves, and he saw how the dead leaves on the forest floor were lifted up and thrown about as it came running; and he lifted his spear and he stabbed out, there and there and there. But the tiger's stripes will hide it in the trees, and so poor Stupid couldn't see where to strike, and so his spear found nothing. And then he felt the teeth and the claws of the tiger, biting and tearing at him, and he dropped his spear and fell down weeping, and so the tiger ate him and we never found his bones."And so she's invented narrative, where one thing happens because of another, because of what we do, actions and consequences; and she's mixed narrative with illustration with metaphor, and what she's done is probably the most important thing that any human being ever did, because she's invented storytelling. And she's also invented fantasy, because there is no such creature as a storm-tiger; but that's what happens, as soon as you start telling stories. They slide away from the strictly factual, they don't worry about what's real so long as they can talk about what's true.

And that's exactly what I've just done here, I've told you a story about the woman who invented storytelling. It isn't real, I made it up. There never was one woman who sat down one day in the firelight with children at her feet and told them a story about her brother Stupid. But there were thousands of men and women and children too who did that or something like it, who learned to use stories to tell each other about the world and its dangers. Stories teach us to be afraid of the dark, but also to look for help in unexpected places; they teach us the value of trust, and the misery of trust betrayed. These are all lessons in life, and in how to live with others; we learn about the world through stories, long before those lessons are reinforced by experience. In books for adults, the lessons can be more sophisticated and less clear-cut, but they don't need to be, and the books are often better where they're not. In writing for children, they can be spelled out, plain and simple; children are far more tolerant. Rudyard Kipling's Laws of the Jungle may claim to be a system of rules for wild animals, for how the wolves and bears, the jackals and elephants and tigers should behave towards their own kind and each other, but of course they're not, they're rules about how people should behave towards other people. And you never need to say that to a child; they know, without ever being told. That's what stories are for, to live inside their heads and make them think a little differently day to day, and they know it as well as we do.

Also, of course, Kipling's Jungle Books are fantasy. The books may be about real India and real Indian animals, but Kipling's animals don't live by instinct, as real animals do; they have a structured and ordered society, with laws that they choose to keep or to break in a very human way, with very human consequences. Most children's books are fantasies, from the earliest fairy tales to the latest Harry Potter, and there are very good reasons why they should be so.

You can say to a child, "Your gang mustn't fight with the gang in the next street," and they will quite probably - and quite properly - ignore you. Tell them that one wolf-pack doesn't fight with another, say that's the law of the jungle and tell them the story to prove it, and they'll spend the rest of that day thinking wolf, playing wolf-pack and not fighting. Fantasy takes them into a better world, a place they're happier to be; it gives them power and strength, it feeds their self-image and so it makes that image true. They believe or at least they make-believe that they are strong, strong enough not to need to fight, and so they don't fight, and so they are strong. If you tell a child about the real dangers that threaten in the darkness, whether it's the tiger prowling outside the cave or the bad souls on the city streets or the airplane with the bombs overhead, they can be seriously and dangerously frightened, damagingly so. But if you tell them stories, tell them fantasies, tell them about the ghost of the old tiger or the city's wicked child-catcher or the fiery dragon in the sky and they'll still be wary and they won't go off alone into the darkness, but they won't be terrified and they won't be scarred by what you tell them. It's a story, it's a fantasy, it's not the real world, and children know the difference between what's real and what's true. They don't believe in ghosts or child-catchers or dragons, any more than they believe in Santa Claus. Not really, not quite. Santa Claus is a story, that means their parents give them presents; all these others are stories too, that mean there is danger out there after dark. That's what they believe, and what they need to believe; the ghosts and dragons are a hook to hang the lesson on.

But you don't need to think so clearly about a thing, to know that it's true. As a child, of course I didn't think about stories as lessons, how to live in the world. Stories were fun, and fantasies were the most fun, what I loved the best.

I grew up in Oxford, in the 1960s. My big sister taught me to read when I was three, and I've been like a boy under an enchantment ever since, condemned to read for a hundred years. The first thing I did in the morning was pick up a book, and the last thing I did at night was put it down, and it hardly left my hands at any time between. I read all through mealtimes, on schooldays I read in the five-minute breaks between lessons, if we went for a walk I took a book with me and read as I walked along; in my free time, I never wanted to do anything else but read. I read fairy-tales and traditional fantasies, books with wizards and elves and dragons; I read ghost stories and horror stories, which are subdivisions of the fantasy genre, specialist classes in the same school; I read C S Lewis and Rudyard Kipling and a whole long list besides. And I read many animal stories, but as I've said already, I think most of those count as fantasy anyway, if the animals talk to each other or do anything that runs counter to their instincts or their natural behaviour in the wild.

I did read other books, of course, that were not fantasy. I read school stories and war stories and everything else I could lay my hands on. My own books weren't enough for me, they couldn't feed my appetite; I read all the books that came into the house, my big sister's and my little sister's and my brother's also though he was five years older than me and already starting to borrow books from the adult section of the library. I never liked my brother much, but I did love his books. His tastes probably influenced me more than anyone else throughout my life. It was through him and his reading that I discovered science fiction, which has been a passion with me ever since; and more specifically, the first time I ever read The Lord of the Rings, it was his copy that I borrowed.

Growing up in Oxford in the sixties, of course I read C S Lewis, and of course I read J R R Tolkien. Everyone did; it was like supporting Oxford United, they were the local team. C S Lewis had been dead for a few years, but he was still known and remembered and talked about; Tolkien was still very much around. I'm not sure how old I would have been when I read The Hobbit, but certainly no more than seven, and possibly younger. I read it, I loved it; I saw it performed as a play by students in Magdalen College deer park, where I'd also seen The Lion, The Witch and the Wardrobe the year before: out in the open, under the trees, with herds of wild deer running to and fro in the background. That was magic, but the books were better. Books always are better; and good books, better books always lead you forward into unexplored territory, new ideas, new books. It wasn't the internet that invented the world wide web; that web already existed, on paper, in all the books on all the shelves in all the libraries of the world.

So I read The Hobbit, and I loved it, and a couple of years later I found The Lord of the Rings on my brother's bookshelf. It's one of those rare books that lives in my memory with a year attached; the hardbacks had been published as a trilogy in the fifties, but in 1968 the first paperback edition came out in one volume, and my brother bought it, and I borrowed it. Well, I say 'borrowed'. I took it off his shelf, and read it; and when I had read the last page, I turned straight back to the beginning and started reading it again. When I'd finished it for the second time and reluctantly started reading something else, I put it back on my own bookshelf, obviously, and it's still there, that same copy, so I guess you could say that I stole it. I prefer to say that it needed to belong to me, it was desperate to be my book. This was true love, in a way my brother could never have understood.

By the time I was twelve, I'd probably read the book a dozen times. In that year, I was enrolled at a rather grand school attached to one of the university colleges, and Mr Gill our English teacher adapted one of Tolkien's shorter stories, Farmer Giles of Ham, into a play for us to perform. It's a classic fantasy about a farmer and a dragon and a king, and I was chosen to play the king. We were a bunch of kids, and I expect we were awful, but we enjoyed ourselves thoroughly; and after the first night, Mr Gill came backstage with this little old white-haired man. And he brought him straight over to where I was sitting taking off my make-up, and he said, "Charles," - they called me "Charles" in those days, which is how you can tell this is a true story, because I'd never admit to it else - "here's someone I think you'd like to meet. Professor Tolkien, this is Charles Brenchley, and I think he's read everything you've ever written."

And it really was, it was J R R Tolkien himself, I recognised him from his photograph, and his pipe. And he sat down, and he fussed with his pipe without lighting it, and he talked to me for maybe five minutes, and I really have no idea what he said, or what I said in response. I expect I asked the usual sorts of inane schoolboy questions, and I expect he gave the usual sort of weary author replies, but it really doesn't matter. For him, he was just meeting yet another obsessive fan, and I don't suppose he remembered it the next morning, or ever thought about it again; for me it was kind of like meeting God.

I have struggled to remember exactly what we said to each other, of course I have; but my heart was racing and my eyesight was blurred, I felt dizzy and sick with excitement, and all I can summon up is an impression, not a memory. To my twelve-year-old eyes, he seemed to be a man who lived in two worlds at once, as if his body was there in Oxford while his mind was off in Middle-Earth. The trouble is, that's so exactly what I would have expected to see, I don't trust even that impression. I think I saw what I wanted to see, rather than what was really there to be seen; but again, that doesn't matter. What's important is that I did meet Tolkien, and that little meeting changed my life.

As I told you, my big sister taught me to read when I was three. I don't remember that, I don't remember the learning process at all, sometimes I almost feel that I was born with the ability to read. What I do sort of remember is suddenly understanding, around the age of five, that these wonderful things called books were actually written by people, in just the same way that I made up stories and wrote them down, and that it was a job, and that you were allowed to do that when you were a grown-up and you could be paid for it too. Ever since then, I have never ever wanted to do anything else with my life, and I never have.

Not much survives from my childhood, apart from my teddy bear. There's nothing on paper and very little left in memory. I know that I wrote in class and out of class, incessantly, unstoppably. I do remember one poem, about an alien who was red on one side and green on the other; I would have been about six or seven at the time, so even then you can see which way my mind was turning. As well as all the fantasies and fairy-tales, I do also remember writing great historical epic dramas about the Romans and the Egyptians, but alas, they're all long lost.

Until I was twelve, then, I knew I wanted to be a writer, but that was about all I did know. I wrote fantasy because that was natural to me, but not with any special passion; I'd have been just as happy to be a crime writer, or a poet, or a playwright.

Then I met Tolkien, and suddenly I knew exactly what I wanted to do with my life and with my writing. I wanted to be a fantasy writer; I wanted to write about dragons and elves, dark lords and barren wastes and giant hissing spiders. In fact I wanted to be Tolkien, and I wanted to write The Lord of the Rings. It didn't seem to matter that the position was taken, the job had already been done; I saw no reason why it shouldn't be done again. A couple of years later Tolkien was dead, so then the position was vacant; and so I spent most of my teenage trying to fill it, writing bad imitation Tolkien fantasies.

It wasn't until I was seventeen that I finally acquired enough self-criticism to understand just how bad and how imitative my work was. This is one of those rare moments that I remember very clearly: because I love the genre, I remember swearing a great oath that I would write no more fantasy until I had a totally original idea, that owed nothing to Tolkien or to anyone else. It was one of those great oaths that you do swear when you're seventeen, that tend to have been forgotten before you're eighteen or else become entirely meaningless before you're twenty-one. This one, though, this one I kept.

I left school, I went to college very briefly, and then I became a writer, as I had always intended to. And I did become a poet, and a playwright, and a crime writer; and I wrote romance and horror and teenage fiction and children's comics and a whole lot else besides, and I never once wrote a word of fantasy. I still loved the genre, I still read everything I could, but all the time I held this quiet little voice in the back of my head, murmuring 'Not yet'. People used to ask me why I didn't write fantasy, and I always just said I was waiting, until I could do it right.

I wasn't actively looking for an original idea, I wasn't consciously thinking about it at all, I was too busy with all the other work I was doing. Subconsciously, though, something was lurking in the back of my head, poised on a hair-trigger, only waiting for the clue that it needed.

When you're a writer, people are always asking where you get your ideas from. It's like a joke, except that it's true, they really do ask; and generally there really isn't an answer.

This time, though, how I became a fantasy writer after so long being everything else instead, where I got my big original fantasy idea from, this time I can answer the question exactly. I was sitting at home in my flat, and I heard the post arrive; and I went downstairs to collect it, and there was my idea, lying on the doormat, delivered by my friendly postman.

Actually it was a four-page brochure, advertising a book about the history of the mediaeval religious wars that we call the Crusades. And I sat there with the brochure in my hands, not really reading it, just suddenly spellcast with the beauty of this sudden idea. I had always loved historical fantasy, where history is mixed with imagination to produce something that's familiar and yet entirely new. It has no elves, no dwarves, no dragons, so it can occupy the same creative space as Tolkien without being in the least derivative. And although many people had written many fantasies based on many periods of history, no one so far as I knew had tackled the Crusades; and yet they were perfect, they were the ideal fantasy environment.

Even without doing any research, just from my general knowledge I could sit there and count points off on my fingers. The Crusaders were mostly young men, trying to build a new country far from home. They were constantly fighting between themselves, and constantly at war on all their borders. They fought for land, as well as for religion; some tried to impose the culture they came from, while others tried to adapt. All of that is historical, and it's already good material for fiction; but it's so easy to make history into fantasy. High Christian practice needs only a little exaggeration to turn it into genuine magic; and the people they displaced, the Arabs had their own magic, based on numerology and astrology, that was very different from the Crusaders' beliefs. And then there were all the pre-Islamic myths about djinns and ghouls and ifrit; all I needed to do was imagine a world where all of that was real, and there it was, that idea I'd been waiting for all those years, all laid out in one morning's work.

It took me another six years to write the books, but that's the way the process works: a few bright flashes of inspiration, and then long slow hours of building and knocking down and building again, one tiny little word at a time.

Tolkien said that a fantasy had to be believable, that the characters had to live in a world you could believe in, a world that would work from day to day. That's why, for example, Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll doesn't qualify as a fantasy. It's too strange and too surreal, the characters move in a dream landscape and behave like figures in a dream, and it's impossible to imagine them having a life outside that dream, living on after Alice has woken up. I think that's perhaps why I never liked Alice, because even as a child I thought that Lewis Carroll was breaking the rules. Even if a story is full of magic, perhaps especially if a story is full of magic, there must be limits to what that magic can do and there must be a logic to it; it has to obey clear and obvious rules. If magic becomes wish-fulfilment, then there's no tension left in the story, because trouble can simply be wished away. Children know that's cheating, they all have their own experience of trouble and they recognise lies when they meet them.

Say it again, a fantasy world has to be believable. We have to know that life goes on there outside the story, when we're not looking. Writing for adults demands a more complex world, imagined in greater detail; I think perhaps that children don't worry too much about what adults do when the children aren't looking. Children's imaginations are freer, more vivid and more accepting, less constrained by experience; perhaps you don't have to work so hard to convince a child that a world is real, or real enough to contain a story. But you do still need to work, and you need to encourage your readers to work also. All a writer can ever do is draw a quick sketch and roughly colour it in; we're all dependent on our readers to build the city, each in their own heads. This is perhaps easier for historical novelists, for crime writers, for those who write about the contemporary world, because they write about real cities, real institutions, hierarchies and social structures that their readers know and understand. We who write fantasy have to work harder, first to create and then to convince. It's still the same job, though, for all of us. Our words draw pictures behind our readers' eyes; we paint with their imaginations.

People used to ask me why I didn't write fantasy; these days I'm more likely to be asked why I do write fantasy, why I don't write serious literature instead. Mostly they don't mean to be insulting, some of them are even trying to be complimentary, in a clumsy sort of way. The question is of course an insult, because it suggests that my work isn't serious, or isn't literary, or both. A couple of hundred years ago I'd have been fighting duels like Lord Byron, to defend the honour of my novels. These days, you just have to live with that degree of ignorance, and learn to smile and move on in a superior kind of way. These people dismiss fantasy because it's all about elves and dragons and magic, while they think that books should be about the great themes of literature: love and death and politics, war and power and pride and decay. What they don't understand is that actually we get to write about all of those great themes too, that's exactly what our own books are about, and we can be as serious about those themes as anyone who gets shelved on the literary side of the library. It's just that we have all the material of the human world to play with, and then we get to write about elves and dragons and magic as well.

Or perhaps they do understand it, and they're just jealous because they know they're missing out, they know we have a connection, a direct inheritance that they lack. Perhaps secretly in the dim critical distances of their skulls they catch a glimpse of an evening sky beyond the cave-mouth, they sniff the smoke of a sullen fire and they hear the echo of an old voice telling an old, old story while the thunder rolls in the hills; and perhaps even they shiver a little, because it sounds so like the roar of the tiger.

More about Fantasy or return to the home page.