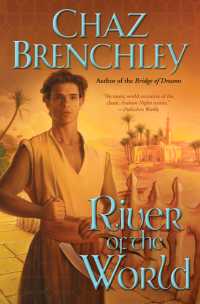

River of the World

The city of Maras-Sund has stood for more than 20 years - two lands joined together by a magical bridge the Marasai used to conquer the Sundain.

But the man known as Issel has magic of his own - an ability to manipulate water - which he will use to free his people.

He finds an ally in Jendre, the daughter of a general in Maras' army and a woman with her own vendetta against the regime. Her sister is held captive along with others whose life essences power the magical bridge between her land and Sund. Her plan: to help Issel enter the palace and break the spell.

Buy the Book

Order River of the World from Amazon.com in a Audible audio edition or Kindle edition.

Copies may still be available:

- in the original hardback edition;

- in paperback;

Or order it from your local bookshop, quoting:

hardback: ISBN: 978-0441014781,

paperback: ISBN-13 978-0441015849

both published by Ace.

An extract to read online

Odd the things she noticed, when she was trying so determinedly not to think. The stream sounded altogether noisier inside the culvert, as though the water flowed more swiftly - and yes, it did, she could see now, where it fell over a lip and was lost in a mist of spray.

The tunnel wasn't so dark as she had thought; she could see into it quite clearly. Perhaps the water reflected some of the day's light inward? No, that would throw it up onto the roof, and what she was seeing was a light rising from below, beyond where the water fell. Perhaps there were rocks down there that glowed slightly, or else something in the water, a weed or a growth of slime? There were fireflies and glow-worms, she'd played with both and kept jars of them to fascinate Sidië; there might be luminescent plants. Or perhaps it was a slave at work in the sewers with a rush-light or a lamp, there must be some way of access...

That light was definitely growing brighter. She was sure, then, that it had a human source; and she was right, because a figure came slowly into sight, beyond the fall.

And hit her head on that low and sudden ceiling, because she'd been watching her feet in the water; and cursed, which was how Jendre knew that she was a girl.

That wasn't right at all, for a slave at work in the sewers. The Marasi didn't send their girls to do that kind of work. And she was wet to the skin, likely wet to the bone of her, but even so Jendre couldn't puzzle out her clothes at all. Clothes declare a person's place in the world; she thought she'd never seen dress so nondescript, so unrevealing.

And more than that, worse than that, the girl wasn't carrying a light. Rather, light glowed within her cupped hands like water, and dripped between her fingers like water, and dribbled down into the stream and was borne away. And then the girl lifted her eyes to see the grille and the daylight beyond, saw how she would need to crawl to reach it; and opened her fingers and let all her light spill out at once, and Jendre couldn't pretend that it was anything but sorcery.

Still, she didn't run. She didn't move at all; only sat where she was and waited till the girl came crawling awkwardly up to the bars, and looked out, and saw her.

Eye to eye, stillness to stillness, silence to silence: how long could that last?

Only as long as it took Jendre to gather her courage and make a move, stand up. And then not run away, but walk towards the girl.

It helped, a little, that the sorceress looked quite as scared as Jendre was, and quite as determined not to back away.

Jendre walked in the water, as the other girl had. Here where the stream dived into the culvert, the banks rose steeply and were even more overgrown. This was the only dignified way to meet, face to face. If that meant wet and chilled from the knees down, then so be it.

She couldn't quite decide if it was very stupid or very trusting, to wade into the same water as a sorceress. Probably both. No matter. The girl had come this far, and if Jendre was right in her private, terrifying guesses, it had been a bold and a perilous journey; she could go this little way to meet her. She had taken greater risks than this, when she'd had much more to lose.

Even so, she wasn't foolish. She stopped a long arm's reach before the iron grille. The girl was closer on the other side, but not close enough to snatch through the bars. If that made any difference, to a sorceress...

"Please," the girl said, "what is this place?"

Jendre thought it was more proper for the intruder to explain herself, but, "This is the garden of the old palace."

"What they call the Palace of Tears?"

"I have heard that, yes." Heard it, used it, feared it. When you were frightened, it was more important than ever to act bold. Her father had taught her that, and so had her life, often and often. She said, "Are you from Sund?"

A moment's hesitation, which Jendre found comforting, that even a sorceress could have doubts, and wonder what was wise to do. Then the girl said, "Yes, I am. Do I need to tell you, not to be afraid of me?"

"No." Telling wouldn't help, fear was just a fact; but the girl had reason enough to be afraid on her own account. The Marasi had never been gentle with magicians, except those they employed. If she was found, the girl's fate would be appalling. "What is a girl from Sund" - that was easier, to call her a girl: she was clearly much of an age with Jendre, even if she had all those mystical wicked gifts of her people - "doing in the sewers of the Old Palace?"

"Looking for a way out."

That was blunt, at least, and Jendre matched it. "I'm afraid these bars prevent you." Blunt, but untruthful; what she feared was the opposite.

"They do. They wouldn't stop Issel for a moment, but -"

But she obviously thought she'd said too much, and that was two confessions at once: one, that she was not so powerful a sorceress, if iron bars could block her; and two, that she had at least one companion who would not be blocked. If he were here, which he was not.

Something to be thankful for, something to fear. Jendre said: "Will you tell me your name?"

A moment's pause, a thought; then, "Rhoan. I'm called Rhoan. Who are you?"

"Jendre." It didn't occur to her to lie. "Truly, Rhoan - what is it that you want in Maras?" Your life must be risk enough in Sund, with the soldiers always on the watch for magic; why would you spit in God's face, to come here?

"Truly? My people's freedom, my city's joy."

"You will not find that here."

"Oh, but I thought I might."

One girl, a sorceress who couldn't make her way out of a sewer? Jendre smiled despite herself, and saw that smile reflected on the other side of the bars.

"You're forgetting," Rhoan said, "I've given myself away already; I'm not alone in here. There is, oh, a full handful of us. And you've told me more than you ought, as well."

"Have I?"

"Yes. You told me that I'd found what we've been looking for. Don't be frightened, we won't harm you, or your people. If these are your people, these Marasi. Perhaps it'll mean your freedom too."

"Do you take me for a slave here?" For a moment, she was genuinely indignant.

"Hiding in the bushes, easing your weary feet in the water... Crouching in the stream-bed, to whisper to an invading stranger... I didn't take you for a high-born lady of the town. Was I wrong?"

Well, no. Neither high-born nor a lady; but, "I was the Sultan's wife, and Maras-born. My father is a general," or was, under the old dispensation. Whether that had carried over to the new, who knew?

Rhoan's lips shaped a soundless whistle. "Ailse told us that the old man's women would be kept here - but I didn't think she meant girls. No wonder you're so unhappy."

"No, you don't understand. It's not for me..." Though it was of course the hopeless search for an escape that had brought her here, and perhaps Rhoan understood her better than she wanted to admit.

"You want to take someone with you. Or more than one. Why not? It'll be an open door."

Jendre shook her head. "Even if we could, there's nowhere to go..."

"Sweet, this is the other side of the cage; there's all the world out here. These are your bars, not mine. Go where you like. We'll help, if we can. If you help us."

"I don't know what you want."

"Just point us towards the dreamers, the magicians. The ones who make the bridge."

Jendre shivered. Was this hope returning to her life, this icy chill down the back of her neck, like a trickle of meltwater? She said, "I can do that, if you or one of you can break these bars. But it is not the magicians who dream, and it is not the dreamers who do wrong. You must not harm the children, you must promise me that or I will show you nothing but guards with swords who hate the Sundain and all their sorceries..."

Return to Home Page or read more about Selling Water by the River